The Judgement

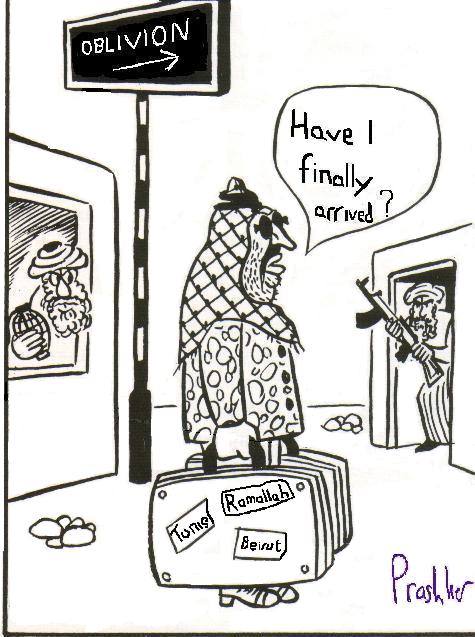

A satirical detective story in which Inspector Julian King seeks to unravel the mystery of the Tarot Card Murders, and comes face-to-face with his own death.

"In form it's a novella - too long to be called a short story, too short to be dignified as a novel; but the length is the least important part. I am fascinated by the ways in which the 20th century and the 13th century live side by side, with airline pilots wearing lucky charms, and people using computers to calculate the secret orthographics of the Bible, and communities that have prohibited the Internet but provide their populace with state-run TV, and the idea of genetic pre-determination as a means of updating the atavism of fate and destiny. Superstition and science cohabiting. So what happens if the evidence for a series of murders runs in both directions? I thought it might be fun to try it and find out. Tongue very firmly pressed to the cheek throughout."

David Prashker

Excerpt: Chapter One: The Temperance

She loved her little lie-in of a Sunday morning more than anything else all week. She liked to lie there, pretending to Bill she was still in slumberland, which she was really, if only that pleasant twilight state between sleep and wakefulness in which you can watch your own dreams like a movie at the cinema. Control them too, sometimes, with a bit of careful directing, so that the bits that came out of the bottom of your soul were less unsettling than a regular dream, and maybe Cary Grant or Gregory Peck could be induced to make a brief appearance, just a cameo mind, with herself in the role of romantic amoureuse.

But not this Sunday, alas. Bill’s snoring had woken her early, and somehow, instead of Clark Gable, it was her son-in-law Roger who went and invaded the dream, with his dirty boots up on the sofa and herself standing in the doorway screaming at him that he’d better be the one to work out how to get the cover off and bloody well take it to the dry-cleaners himself to get his beer-stains out. She had, in fact, been meaning to for several weeks now, provided that it wasn’t too expensive. Roger was coming to lunch with Sally and the kids, she remembered, which set her mind to thinking rather than to dreaming, and that in turn made her register that her bladder was rather full. The bedroom was like an iceberg. The cat had left its moulting hairs all over her dressing-gown; and a mouse, or the bloody remains of a mouse anyway, on the floor of the bathroom. It was clearly going to be one of those mornings.

By this time all dreams had faded, not just the impossible dreams of Hollywood lovers, but even the more ordinary, though no less fantastic dream, of staying warm and snuggled up till nine o’clock without Bill trying to get his leg over for what he called a Sunday special. There was the roast to put on, for one thing. And Sally did like her bit of Yorkshire pud.

In the kitchen she put the kettle on the gas, then dragged a dirty cup out of the pile of washing-up that Bill had said he’d do, he’d promised, as soon as Match of the Day was over. God, but he could be a right lazy bastard when he was of a mind to it! There were sticky lumps of mashed potato on the saucepan that he couldn’t even be bothered to leave soaking overnight. And her cereal bowl - her own one, the one he knew she never let anyone else use, the Royal Wedding bowl, that Sally’s kids had given her – it was just sitting there in the middle of the basin, all filled with his toe-nail clippings. She could have killed the selfish sod. But washed the bowl, dried it, admired the couple pictured on it who could themselves have been a pair of Hollywood starlets, then filled it regally with Corn Flakes, and went to the fridge for milk. Bill had guzzled that too. There was his mug, sticky with hot chocolate, perched on the telly where he must have put it down when he switched the set off. She put her hands on her hips and moistened her thin lips, laughing and frowning in the same breath. This, after all, she reflected, is how Royal Couples and Hollywood Starlets no doubt end up as well. She could just imagine Princess Di complaining to Charles about his leaving the cap off the toothpaste yet again. And no doubt Cary Grant was just as lazy as her Bill when it came to changing his underpants regularly!

Because she was a logical woman, not much educated of course, but she knew what she knew, it was easy enough to separate out the portions of dream and the portions of reality without getting them too confused.

“I’ll never be able to eat out of that bowl,” she had said, when the Christmas wrapping had first come off. “You can’t eat off royalty. It wouldn’t be right.”

But she was practical too, and besides, it was perfectly obvious that she was just saying it. Nor did the royal pair seem to mind when their faces were daubed with sticky pudding or smeared with custard or forced to endure an attempt at crème brûlé which even Sally, who liked sour cream, had been quite unable to swallow.

There was a simple logic to the mess in the kitchen too. Chelsea, she realised, must have lost again. If they’d won he would have done the washing-up just to give himself the excuse to mumble under his breath an interview with Jimmy Hill about how well the boys had done and whether or not the second goal had been offside. He thought she couldn’t hear him, but she always could. It was quite funny really. Sometimes she would stand there for ages, listening to him talking to himself out loud when he thought no one was about. Football. Boxing. Even the cricket. One time she’d come home early from work and there he was in front of the box with the volume turned right down and him doing the ball-by-ball commentary like he was Richie Benaud and Brian Johnstone all rolled into one.

But Chelsea had obviously lost, he hadn’t done the washing-up, and he’d gone and guzzled the whole pint of milk that she’d been saving for the Yorkshire pud, and if she went back to bed and snuggled up to get warm, the fat slob would start pawing her and she wasn’t in the mood.

Upstairs, Bill turned over in bed and farted massively. The fat frump who’d been his wife for more than forty years just shook her head. If she had known he would turn out to be a disgusting slob she would never have agreed to marry him, but in those days he was really rather suave and debonair in his demob civvies and with his stories of the war in France. Now the only fighting he did was down the Elephant & Castle on a Saturday night if Millwall had a home game and lost and needed some Chelsea supporters to take their anger out on. Which was generally every other Saturday. And the selfish sod had drunk the milk that she’d been saving for the Yorkshire pud! As though saying it for a third time would make the milk mysteriously reappear.

So she opened the front door, for the purely innocent purpose of putting out the empties and picking up the bottle of semi-skimmed she had quite forgotten she had asked Patel to drop by when he sent his lad round with the Sunday papers. She had grabbed her overcoat, because the house was warm enough without a dressing-gown, but outside it was frankly parky, and now she had to hold the overcoat tight at the waist with one arm, which meant stooping slightly, and reaching down awkwardly to put the empties down and pick up the other pint of milk, all with one hand. It was foolish really. It would hardly have taken any trouble to button the coat and put down the empty with one hand and then pick up the fresh bottle with the other. But she was feeling tired this morning. So she stooped in that lazy, awkward manner, trying to put down the one bottle and pick up the other with the same hand. And both of them slipped. And the new bottle broke. The drips of milk and the snow-flakes of frost were hardly distinguishable, white on the white ground.

The woman went back into the house, muttering oaths under her breath. A moment later she returned, bearing a dustpan and a brush. Bending, still awkwardly, she collected up the shards of broken glass. Then, suddenly, something in the street caught her attention. She looked up, and for a moment remained perfectly still, as if the cold morning had frozen her like a statue in that sub-suburban street. Her face showed more surprise than fear. Clearly what was about to happen was the most unexpected, the most improbable thing in all the world, less likely even than Charles Bronson or Paul Newman or her husband getting up to help. Nor did her expression change when the single bullet was fired. Simply her mouth fell open, her body crumpled to the floor, her dentures slipped from her mouth, and a trickle of blood oozed slowly from the hole in her forehead.

The name of the deceased was Marion Shirley Coates, aged 62, of 38 Stanley St, Clapham, SW4. No one claimed to have witnessed the actual murder, though two neighbours made statements to the police concerning what they had seen and heard of the befores and afters, and a third did come forward some time later, in response to a reconstruction on the BBC Crimewatch programme and an appeal for information in posters put through letterboxes by the local constabulary; but all he could say was that he had heard a bang around that time, that it had woken him, that he had presumed it was just those bloody delinquents from the council estate letting off fireworks again, and had gone back to sleep. Bill Coates, the deceased’s husband, was detained for questioning, but released without charge after several hours. The time of his wife’s death was recorded by the emergency services as 6.03am on March 1st 1987. The verdict on the cause of death was left open, pending further police enquiries. No obvious motive existed to help the police with those enquiries, but there was one curious fact, the presence of a Tarot card, specifically the fourteenth of the Major Arcana, The Temperance, which some anonymous person later in the day posted in a plain manila envelope through the door at Stanley Street.

|

|