The Argaman Quintet: The Flaming Sword, A Little Oil & Root, The Chronicle of the Kingdom of Alphalia, The Hourglass, Going to the Wall.

From the stetls of Eastern Europe, through resistance to the Nazi Holocaust and the birth of modern Israel, to the plight of Eastern European Jewry under Communism, five novels which explore the moral complexities of being Jewish in an anti-Semitic world.

A Little Oil & Root

David Jacob grows up believing he is an Englishman, the son of Max and Miriam Jacob, destined for the world of Jewish scholarship and academia. But travelling to Israel for the funeral of Ari Ben Aaron - the former Bernhard Aaronsohn, author of "The Flaming Sword" and "The Chronicle of the Kingdom of Alphalia", survivor of the Jewish resistance movement in Poland and the insurrection in Auschwitz, fighter in the Israeli War of Independence and one of its great modern artists - David discovers his true identity in the ashes of the Holocaust, and experiences the reality of a two thousand year Jewish dream in the modern State of Israel.

"I lived for more than five years in Israel, through the 1973 Yom Kippur war, the year of katyusha rockets out of the Lebanon before the War of Peace for Galilee in 1982, the war itself that ended in the terrible calumny of Sabra and Shatila. I was part of the last years of the great experiment in cooperative living that was the kibbutz movement, and the transition from David to Goliath as the state created by survivors and refugees transformed itself into a regional super-power. In any other country in the world, one can be a patriot who criticises, a lover of the country deeply at odds with many of its component parts. Not so easy with Israel. Yet how else can one write honestly, and helpfully, but by painting its glorious face, warts and all."

David Prashker

Excerpt: Soon after his return to Israel, David visits his "father" in hospital:

Ari in hospital, seeing him for the last time exactly as I had encountered him that first time, almost twenty years previously (in Cambridge, for the record), sitting, or rather propped up, his forehead bound in white bandages, his body wrapped - I almost wrote mummified - in a white surgical gown from which tubes and plastic wires unfurled like the beads of a phylactery; but in a state of complete obliviousness, like an early Frankenstein. Coma is the midway point between sleep and death, the limbo-state; but while Ari had apparently given up the long struggle at last, the doctors and nurses were in no such mood of resignation. Modern science has taken on the great battle and, to judge from the sophistication of its armoury, it must stand at least a reasonable chance of eventually triumphing. Through Ari's nose and mouth a network of synthetic arteries fed him the liquids that his body required, while another, emerging from the sheets at the foot of the bed, served as a gutter in which the waste could be siphoned off again after consumption (yes, but can the will, the spirit, be nourished intravenously?). Wires strapped to the machine that his body had now become, dials registering and controlling heart-beat, pulse-rate, blood-count - it was as though he were being flown on automatic pilot.

Yet in his face there seemed to be something of disdain, of mockery for all this, an almost Buddhist glow of quiet resignation, and I half-expected him to sit up all of a sudden, to throw off those absurd shackles and cry out:

"Tell them, David, tell these fools of doctors. My blood is plasma, fed by liquid fire. Tell them I have asked God to pray for the success of their technology. Tell them their medicine is only magic with Latin names - they cannot repair a broken heart with magic. Tell them to dip my spirit in the fire, heel and all. Tell them they can never defeat Death, but only, at best, postpone it. Tell them, David, tell these fools of doctors. I ate my worm years ago. I am ready for the worm's revenge."

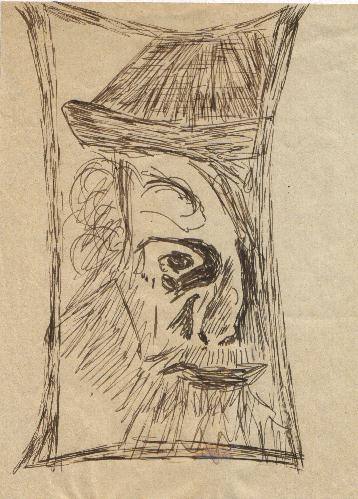

But he continued to lie there motionless, like an effigy of some martyred saint, his hands spread out in front of him on the bed-sheets, and he seemed to be examining them with all the studiousness of a gypsy devining the Tarot. Yet there was no mistaking the grin, as though dying were some private joke that he was playing on all of us, as though the last paroxysms of his haemorrhage were also the first tremors of laughter, an explosion of irony that would leave his tongue forever frozen in his cheek. The face seemed to have been cast in gypsum - unless that was simply the effect of so much harsh electric light - the body composed as though he were offering himself to the world as a last, abortive attempt at sculpture, the one art-form he had completely failed to master. He lay so still, one had the impression that the death-mask was already in place; but it was a false mask, a travesty of his true face. The nose had been made heavy and jagged by surgery, the high forehead raised higher still by the shaving of his prematurely white hair, the human being reduced to little more than a complicated structure of bone and tissue, a web of arteries fuelled by organic chemicals. Almost by instinct my mind turned back upon that catalogue of Ayishah's, the war-paintings from Treblinka and Auschwitz, from the Alt-Aussee especially, those ghouls and ogres and troglodytes (those scarecrows) that had so shocked the art world when Howard Vaughan exhibited them in London in 1947 - and suddenly there seemed to be something macabre, something grotesque, not in the form that his own death was taking, but in the way the corners of his mouth had extended into the ambivalence of a smile. As a dog is said to take on the characteristics of its master, so he appeared to have entered into the fugue of his own works, to have become one of his own more gruesome creations. So thin and wasted was he, so forlorn in defeat, one would have said that his body had at last succumbed, as his spirit had so adamantly, so valiantly refused to do, to the horror and brutality of the camps. And yet he lay there, one of his own paintings, one of his own worst memories struggling in vain to be incarnated, grinning - it was as if to say "I told you so".

Seeing him like this was to be punched in the ribs by depression. The longer I remained, the harder it was to bite back my tears. Yet I knew that he wouldn't have wanted me to weep for him, and I could easily imagine him reproaching me for it, chronically indignant as he seemed always to have been, saying something along the lines of:

"Stop looking so god-damned glum will you. I'm the one who's dying! Sentimental nonsense! Can you hear me weeping about it? Damned right you can't. Go and read a page of Lawrence and stop blubbering. And stop trying to make me feel guilty about it – I'm not doing it on purpose, you know. All you people who sit in hospitals feeling sorry - and not for the patient, but for yourselves. Rest in peace? Go away, damn you, and let me die in peace."

I wanted to speak to him, but there was nothing to say, no likelihood that he could even hear or understand. I felt like Isaiah in that parable he called "The Message" - but unable to do or say anything to console either of us, let alone to encourage him. So I allowed the silence to continue its rapt vigil, our communication to remain as impersonal as it had been through so many years of corresponding - indeed, so far away from each other did we seem, so impregnable was the shell in which he had oystered himself, that I felt tempted to put a stamp on the silence and post it to him. He was approaching death with the alacrity of a broken-winged bird, and I knew that I was seeing him now for the very last time. I wanted to offer up a prayer for him, a psalm of farewell, but he wouldn't have thanked me for it. Yet something between prayer and silence was plausible, and sitting on the bed with his hands in mine I recited out loud those lines of Bialik, so difficult to render in English:

"Then the torch was extinguished

the gate swung open

and a light gleamed from within;

And he lay down his body

like a flaming sword

and dropped at the threshold of the abyss."

I pronounced the words "goodbye, father" - both of which sounded entirely strange upon my lips - then turned and left.

|

|