The Argaman Quintet: The Flaming Sword, A Little Oil & Root, The Chronicle of the Kingdom of Alphalia, Going to the Wall, The Hourglass.

From the stetls of Eastern Europe, through resistance to the Nazi Holocaust and the birth of modern Israel, to the plight of Eastern European Jewry under Communism, five novels which explore the moral complexities of being Jewish in an anti-Semitic world.

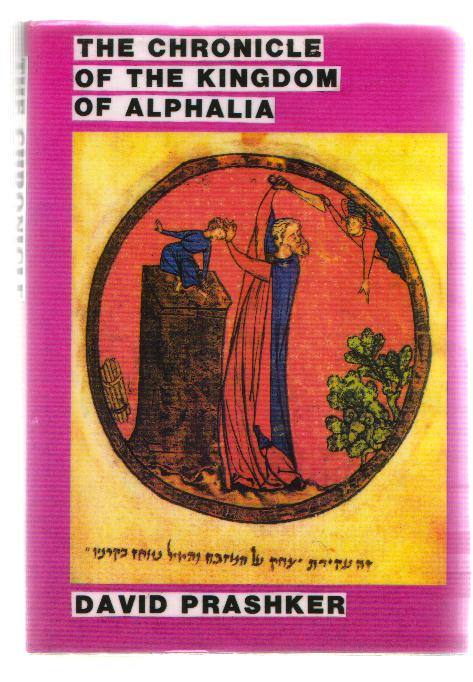

The Chronicle of the Kingdom of Alphalia

When his village is destroyed in an Easter Sunday pogrom, and he comes out of hiding to discover his wife and child brutally murdered, Yakov Baritzchak decides he has had enough of being Jewish. Now known as Mikhail Lubov, married to Catholic Marja and owner of a small subsistence mine, he tries to rebuild his life. But the Jew in him will not go away, and through a network of secret Jews he finds a way back to the man he once was...until the cycle of eternal recurrence brings him all the way back to being, once more, Yakov Baritzchak.

"This is Ari Ben Aaron's novel as much as it's mine. Just as I had him write his 'auto-mythology' in the several parts of 'The Flaming Sword', revisiting his own life in order to become reconciled with it, so I needed him - or he needed - to revisit the sources of that life, the one his parents had fled, the life of the stetls of Poland which anti-semitism and the loss of Israel had rendered compulsorily religious, the one that was ended historically by Hitler and Communism, but even more so by the establishment of the State of Israel. The key question for every Jew post-Holocaust and post-establishment of the State of Israel, the question that two-thirds of world Jewry still do not wish to ask, is now the most important one of all for every Jew: when the Temple was destroyed, the Sanhedrin established Judaism as a 'substitute' for national identity; now that we have a national identity restored, why do we still need the 'substitute'?"

David Prashker

Excerpt:

The rain did what rain tends to do; it lashed incessantly for forty days and forty nights. But at last Mikhail Lubov was able to continue his journey from Irgendwobad to Nirgendwald - though precisely what took place there is of such negligible consequence to our story that I shall gloss over it and rediscover our hero, if I may call him that, returning home some few days later, his cart now filled with bargain-basement furniture at one end, a dozen and a half bantam hens in a wire and timber coop at the other, watched over by a heavily pregnant milking cow he had decided to name Leah, and a milking sheep he had decided to name Rachel – Hebrew etymologists will acknowledge that this displayed much erudition on his part. The storms had flooded the main road, at one point brought down a tree of such immense size it not only blocked the road, but shattered a number of rocks and boulders at the verge, so it seemed the hand of God was visible again, and who could foretell what that portended? Mikhail Lubov was obliged to make a detour through the hills, following a side-road that wound between the fields and woods and marshes. His horse did not stop complaining. The axel of his cart moaned even louder than the horse. But Mikhail Lubov was unconcerned, for destiny was guiding him, what is meant to be is what is meant to be, and if your journey through the wilderness seems somewhat circuitous, at least you have the reassurance of historic precedent. Indeed, what started as a minor inconvenience ended as a major stroke of good fortune, for right there, among the rocks and boulders and the mud splashing on his boots, he came upon a fold in the hills, where the stony soil was baked as dry and brown as a Pesach macaroon.

To all intents and purposes it was simply a geological fault, an obscure patch of wasteland lost in the background of dry hills behind the still more obscure village of Rozterk, a hump-like ridge that protruded from the valley, with a solid majority of stalwart, ancient sycamores, and a liberal spread of sleeker, greyer ash. Stones for the most part, or an occasional wild cabbage, lost among the hedgerow. Had it not been for a fox that came scampering out of the long grasses, its red brush glistening in the sunlight, Mikhail Lubov probably would not have noticed it. But the fox drew his attention. He even went so far as to stop the cart, and stretch his legs, and relieve himself against a convenient bush.

So that he had to look at something.

Not that there was much to look at. A wasteland that vaguely resembled his own life, in essence if not in substance, and an even vaguer notion that was beginning to take root in his more fertile imagination, fecundated by his fiancée’s hopes and dreams, substantiated by the rainbow which, even now, was establishing its covenant in the arc of the skies. This was a different kind of starkness from that of his own farm - inert because torpid. This land, as supple as a taut muscle, seemed as if frozen on the point of growth, like a morning-flower waiting to burst its cocoon. He only had to touch it, he felt, and the muscle would uncoil, arm and land united in one upsurging movement. Then he did touch, if only a handful of damp mud and a tuft of withered grass, touching because he could not convey his intuition in the abstract.

Or revelation was it, there among the dandelions and buttercups?

Not to mention unseen stinging nettles (because there are always unseen stinging nettles).

A veritable miracle nonetheless, a moment of genuine inspiration. One that belonged to him, but might also have reinstated God.

But for that he needed proof first.

Yet his eyes had made contact.

His hand had turned black.

His mouth was pronouncing the Word - or word anyway.

And the word was coal.

It required no burning bush, no flood, not even the still growing rainbow whose pot of gold he seemed convinced he had discovered.

For it was obvious, to anyone with eyes to look, just from the lines and creases and the colours of that crust of earth.

Coal.

As if the fates had sprung this on him as a reward for his feat of story-telling.

Coal.

The very word fired his imagination. Coal could be extracted from inertia and used to generate energy. Coal was the eternal blackness transformed into the sun’s fire. Coal was dead matter subdueable by living force. Simply by digging deep, by ploughing the furrows into trenches, a man could be part of progress, part of the great industrial revolution - a man of wealth and glory and distinction such as the Goyim took their hats off to, and welcomed in their private clubs. Alright, perhaps not that, but definitely the taking off of hats. And why not try it? It was the logical next step, and frankly anything was better than Peraotski. Mines were being opened everywhere - deep, dark, subterranean chasms in which men excavated the skeletons of Mammon and Mephistopheles, plundering the fuel that stoked the fires of Hell until eventually they hoped to smother them (this was the kind of language being used at the time, in poetry as well as tabloid newspapers: ridiculous hyperbole I know; but what can you do?). Coal was progress, whereas agriculture, the blunt implement that had kept his family just above the bread-line for generations, agriculture was a form of apathy.

Mikhail Lubov’s heart was positively fluttering. For suddenly the whole of his future life had opened up before him.

Or a hole in the ground anyway.

It was as if his marriage had just been corroborated.

|

|