A Myrtle Among Reeds

An account of the history and nature of Jewish prayer, explained through a prayer-by-prayer analysis of the traditional "shacharit" - morning - service.

"In April 1990 I took up the post of Housemaster at Polack’s, the Jewish boarding house at Clifton College in Bristol, England. It was a teaching post for which my experience and background hadn’t really equipped me. As well as teaching an academic subject in the school - in my case English, for which I was qualified - it required the pastoral supervision of several score of teenage boys and girls, the boys living in my house alongside my wife and children; plus the leadership of daily synagogue and all other aspects of their Jewish lives. I had no training for this, either as a Rabbi or a teacher of Jewish Studies. My only visits to synagogue in the previous twenty years had been as a tourist. I entered with the taste of pork on my lips, not entirely certain about the status of my faith, and a failed Zionist – I had left Israel disillusioned five years previously. My Biblical Hebrew, abandoned after my orthodox Bar Mitzvah, was at best rusty; my knowledge of modern Ivrit, the reinvented language of contemporary Israel, amounted only to the spoken. I had brought with me neither skull cap nor prayer shawl, for I simply hadn’t remembered from my childhood that these garments would be needed. And yet, there I was, the world’s worst yet most committed Jew, employed not quite as the Rabbi though certainly as the Rav, the father-figure to a generation of teenage boys and girls, many of whom felt exactly as I did about synagogue - and didn’t lack the forwardness to stand up and express it. But where they could choose neither to learn nor to participate, my duties and responsibilities placed me on a learning curve that would have taxed the angel at Penuel.

"I was raised in a traditional Jewish home, one that was entirely comfortable with its high level of hypocrisy. On Saturdays we avoided synagogue while going to support our favourite soccer team religiously; but Sundays my mother had a WIZO meeting, my father a bridge tournament to raise funds for Soviet Jewry, and I was at B’nai B'rith. At home we distinguished milk from meat, down to the very drying-up cloth, but away from home we were accomplished at distinguishing langoustes from mere langoustines, and were amongst the earliest masters of the esoteric art of eating pork spare ribs with chopsticks. In preparation for my Bar Mitzvah I’d been thrown out of three Orthodox Sunday Schools, because my father wasn’t having his son wear tsitsit or lay tefillin, but no way was he sending me to Reform either. After my Bar Mitzvah I swore never again to set foot inside a shul or have anything to do with Judaism - and proved it by becoming, at sixteen the Chair of my local B’nai B’rith chapter, at eighteen a volunteer in the Yom Kippur War, at twenty a campaigner for Soviet Jewry, at twenty-five a kibbutznik on the Lebanese border, and by the time I was thirty the author of four novels, all of course on Jewish themes. And then I came to Polack’s, as Housemaster and spiritual leader.

"Five and a half years in Israel had made me fluent in modern Ivrit; and because the modern was founded on the classical when it was reinvented at the beginning of the 20th century, it didn’t take long to learn the basic prayers verbatim, first to read, gradually to chant. By the end of five years there wasn’t a service that I couldn’t lead, even allowing for complex variations to the ritual, a full moon falling on the Sabbath of a leap year, a new moon on the interim morning of a pilgrim festival. Why, I could daven every inch of Yom Kippur without so much as swallowing, all the way from Kol Nidre to Ne’ilah! And all the rest could be evinced from books - history, culture, laws. Ten years after I arrived, naïve and ignorant, at Polack’s, the learning curve had not yet flattened out - nor will it ever - but the steepness of the curve had started flattening. To teach others, I first had to teach myself, and the evidence of GCSE and A level results, the quality of Jewish life at Polack’s, the success of DAVAR, the Jewish Institute in Bristol which I co-founded in 1994, provided testimony. It had taken ten years, but I felt that I knew, by no means everything, but everything that was necessary to the job. That is to say, I knew 'what', and 'how' and 'when'. It had never once occurred to me to question 'why'.

"Daily morning service, plus Friday evenings and the whole of Shabbat morning, every festival that fell in term-time, Yom ha-Sho’ah, Independence Day, Grace before as well as after meals - after a while it’s very easy for prayer to become little more than a habit, a routine like washing one’s teeth, a mechanical function in which one mouths the words, but chewing, never savouring – rather like school food. The one who prays without his heart in it becomes a function of the liturgy, a part of the furniture of the synagogue, inexorable but inanimate. Ten years after I came to Polack’s, I began to feel this happening to me. And I didn’t like it. Judaism speaks of kavanah, the intention behind prayer, and I was aware that my intention was increasingly to get through the service without losing my temper with those who constantly chattered and fidgeted and interrupted. And I didn’t like it.

"Apparently, I had reached the end of that particular phase of learning, and the time had come to stagnate or develop. When I began, I had needed to learn the letters of the alphabet, then whole words, then the tunes that accompanied the words, and then the correct order and especially the variations of the words in given circumstances. Whether following the parallel English translation, or simply from understanding the Hebrew, I had also come to grasp the meanings of the words. But what of the meanings of the meanings? Where did the words come from? Who put them there, and why, and when? I found myself needing to understand the nature of my habit, in the way a caffeine addict will explore a dozen brands of tea, and want to know where the leaves were grown, how composted, where packaged. So with these prayers, why did we stand or sit, why sing or speak or chant, why silently, why in this order, why on these days, why, in short, did we repeat day after day this strange and anachronistic ritual that seemed to occupy no sensible place at all in the rational, technological world that we inhabited between prayer services, but which nonetheless gave to our lives a spiritual dimension that was miraculously deeper and more personal even than listening to Mahler or to Leonard Cohen. But why, why? Why these silly superstitions like kissing a dropped prayer book or covering the Torah scroll while blessing the one who has been called up to read from it? Why compulsory silences at certain times? Why so much anarchic but tolerated coming and going, and then, at certain times, an absolute injunction against entering or exiting the synagogue? Why keep the head covered in synagogue when every other religion removes its hat? Why the variations in dogma (and in dogmatism) between communities? Why? Where was it written? Did God tell us to do these things at Sinai? And if not God, then on whose authority? I had become deeply curious, and deeply puzzled too. Doubts as to the purpose and validity of all this liturgy and ritual, doubts harboured secretly for years and years, unballasted themselves and floated to the surface.

"I could have gone to the Rabbis, of course, whether the contemporary amorim and tana’im or the greater sages of the past, but they would have given me their answers, and I needed mine. So I began to keep a notebook, working through the prayers one by one, trying to find their source, their intention, learning about their authors, understanding how the words had changed over the course of time - and always, because this was about my own growth: my reaction. This piously irreverent book - an act at once of faith and of protest - is the consequence.

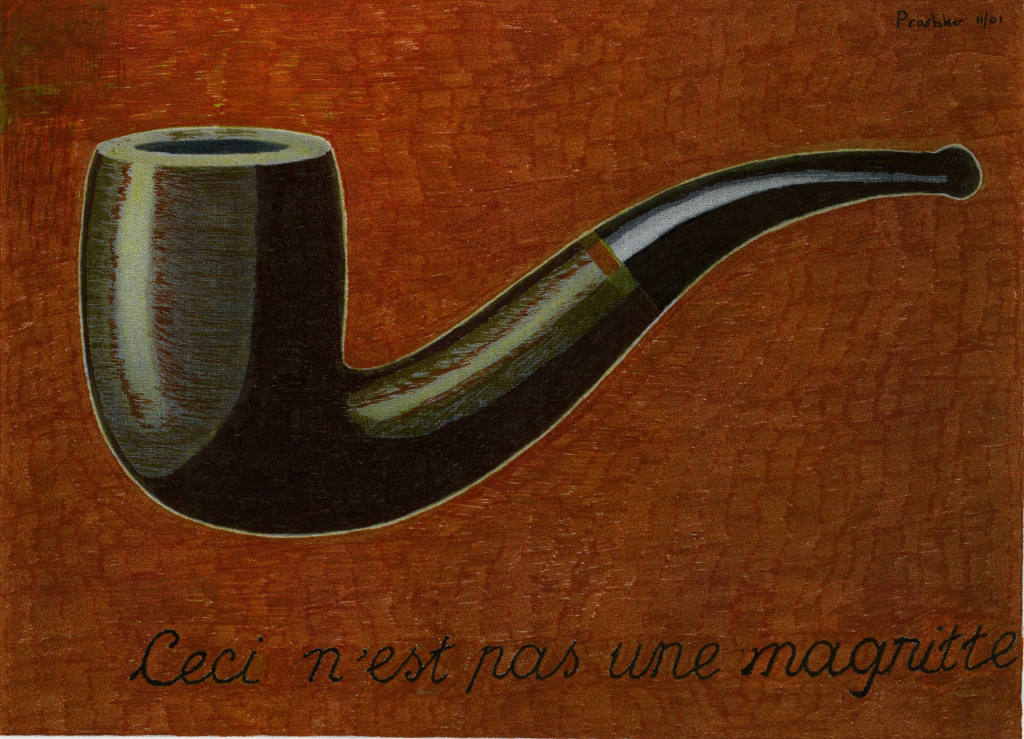

David Prashker

|

|